What is acne vulgaris?

Acne vulgaris or common acne is a chronic inflammation of the hair follicles and their associated sebaceous glands [2].

Acne vulgaris are also known as pimples, spots or zits.

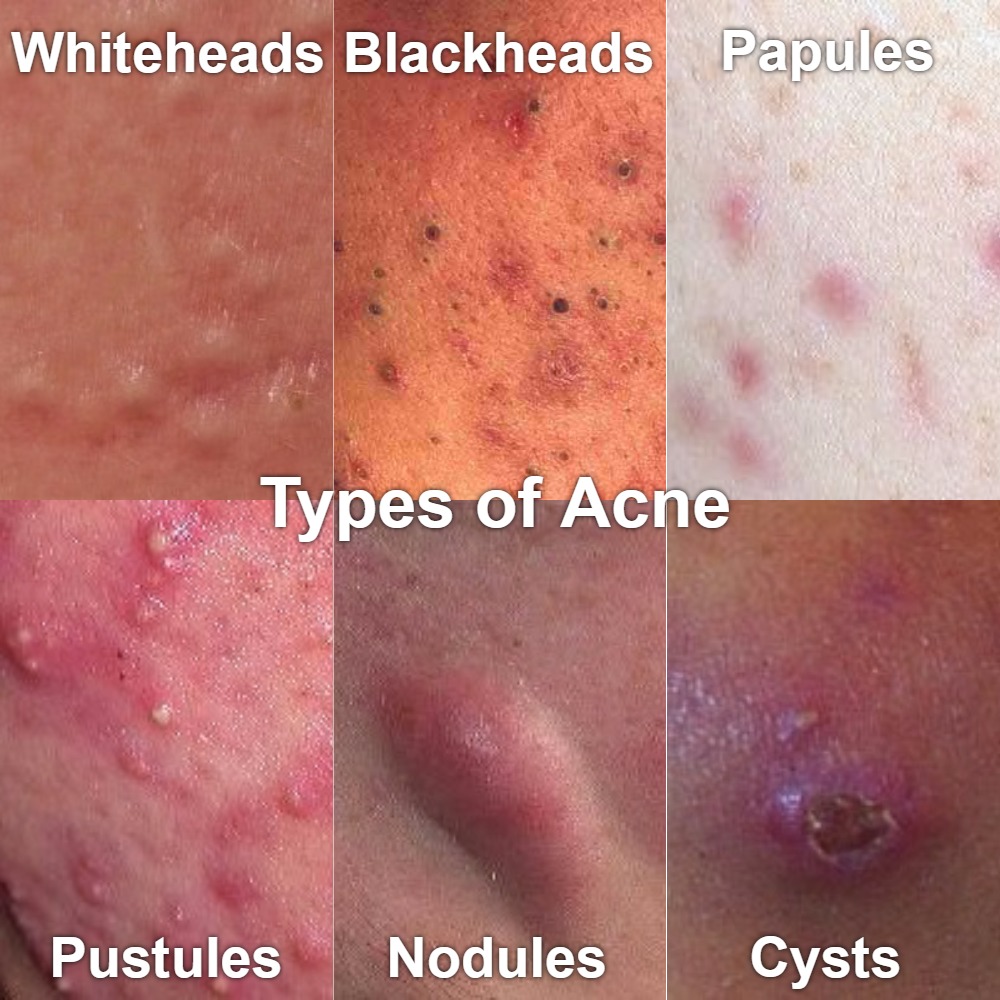

Acne Types and Symptoms

Acne appears as red, white or black and sometimes itchy or tender blemishes on the face, neck, shoulders, upper arms, upper back or chest [1].

Acne most commonly appears in teenagers (boys and girls) usually after the age of 12, but sometimes as early as at the age of 8 and mostly disappears by the age of 25 [2,100]. Adult acne can persist over the age of 40. Infant acne can appear within first few months of life..

Acne forms [1]:

- A whitehead or closed comedone appears as a white bump, 2-4 mm in size.

- A blackhead or open comedone appears as a black dot (1-2 mm); the black color is not from dirt but the oxidation of oil when it comes in contact with air; white greasy material can be squeezed out without popping.

- A papule appears as a flat red bump (2-4 mm).

- A pustule (a pimple) appears as a small red bump with a white center, which is filled with pus.

- A nodule or a cyst appears as a tender hard lump–5 mm or larger–under the skin.

- A cyst appears as a soft lump.

Picture 1. Types of acne (modified from DermNet NZ, CC license)

Acne is not an infection, so it is not contagious. A similar condition–bacterial folliculitis–is contagious, though.

Mild acne is noninflammatory acne, which includes open comedones (blackheads) and closed comedones (whiteheads) limited to the face.

Moderate acne is inflammatory acne, which includes papules (red bumps) and pustules (white blisters) on the face or trunk.

Severe acne is inflammatory acne, which includes nodules or, rarely, cysts, which both appear as underskin lumps.

Acne conglobata and acne fulminans are very severe types of acne, which mainly occur in adolescent males. Painful, crusty and bleeding acne suddenly appear on the back, chest and neck; other symptoms can include joint pain, fever, enlarged liver and spleen [13]. Possible triggers include drugs, such as testosterone, anabolic steroids and a reaction to oral isotretinoin [98].

Picture 3. Acne (papules and pustules) on the forehead

(source: Wikimedia, CC license)

Picture 4. Acne conglobata on the back

(source: Wikimedia, CC license)

Complications

Acne can be infected by the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus; the condition called bacterial folliculitis, which may look similar to acne, appears as itchy, tender red bumps with white pus-filled centers. The infection can heal spontaneously in few weeks, but you can speed up recovery by applying an ointment containing the antibiotic mupirocin.

When acne heals, they sometimes leave dark red spots (hyperpigmentation), which may need several months or years to disappear [2].

Acne cysts and nodules, but sometimes also mild acne, can leave permanent scars [1]. The risk of scars increases with early-onset acne and acne popping [2]. Early treatment with isotretinoin decreases the risk of scars but it does not treat formed scars [2]. There is INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE of the long-term effectiveness of skin needling, chemical peeling, laser therapy or injectable fillers in the treatment of scars [16]. Some scars can be reduced by plastic surgery.

What causes acne?

The exact cause of acne is not known, but the risk factors can include [1,2]:

- Genetic predisposition

- Seborrheic dermatitis or other causes of oily skin

- Apert, SAPHO, Behçet and PAPA syndrome

- Hormonal disorders (acromegaly, Cushing’s disease, polycystic ovary syndrome, pituitary adenoma, etc.) and hormonal drugs (steroids [prednisone…], progestin-containing contraceptives, anabolic steroids…) causing “hormonal acne“

- Other drugs and supplements [10]:

- Antidepressants: amoxapin, lithium

- Antiepileptics: carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital

- Antituberculous drugs: ethionamide, isoniazid, rifampicin

- Azathioprine

- Cyclosporine

- Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors

- Halogens: iodides, chlorides, bromides, halothane

- TNF-alpha inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab)

- Vitamins B6 and B12

Acne Triggers

In susceptible individuals, the following may trigger acne [2,4,5,6]:

- Psychological stress, such as before school exams [70,71], and conflicts in relationships associated with anxiety, anger and frustration

- Oil-based and other occlusive cosmetics (certain moisturizers, foundation and pomades) and sunscreens and other products that irritate the skin

- Pressure of the clothes or skin scrubbing

- Sun exposure

- High humidity or air pollution

- Premenstrual syndrome (before the period)

Although there seems to be insufficient evidence, several studies suggest the following dietary factors may aggravate acne:

- Irregular dietary patterns [60]

- High-glycemic load diets (soda, sweets, deserts and other foods high in sugar, white bread, biscuits and other baked goods made from white flour, white rice, potatoes); they stimulate insulin, IGF-1 and androgen hormone release and can thus trigger acne [15,60,61,62,65,67,73,87]; but some studies have found no harmful effect [66,85]

- Dairy products, such as milk [64,67,86], ice cream [67], cheese [60,84] or protein-calorie supplements (whey) [63,81,83] may trigger acne because they contain the growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) and steroid hormones from cows; they also raise the blood insulin levels, which all stimulate oil secretion by the sebaceous glands [60,61].

There is less evidence about the following possible triggers of acne:

- Iodine (in salt, milk and seaweeds) [60]

- High-protein diets, especially animal protein high in the amino acid leucine [81]

- Diet high in saturated and trans fats and low in polyunsaturated omega-3 fats [60,74]

- Chocolate (milk or dark) [64,67,88,89]

- Nuts [60]

- Pork and poultry [60]

- “Junk food” or fast food (pizza, French fries) [60,64]

- Cigarette smoking [55,56]

The following probably does not trigger acne [2,3,5]:

- Greasy foods

- Eggs

- Gluten

- Caffeine (in coffee, tea, cola and energy drinks)

- Excessive sweating

- Poor skin hygiene

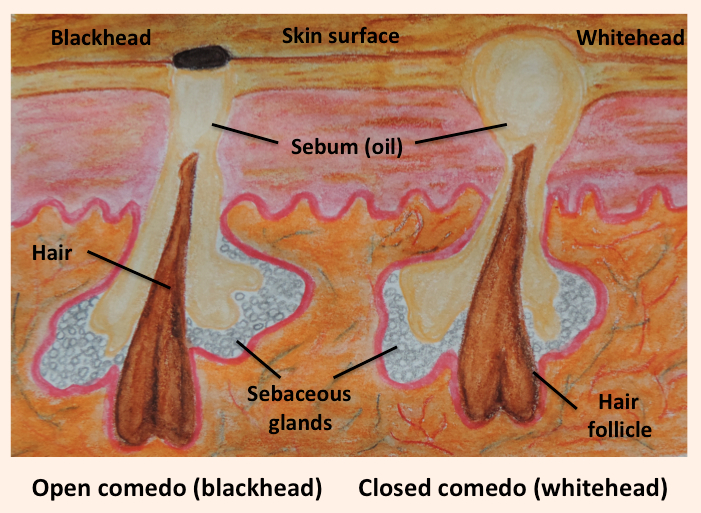

Pathophysiology: How does acne develop?

Acne develops when oil (sebum) and dead skin cells build up in the sebaceous glands and clog them [17]. The following mechanisms are likely involved:

- Increased production of sebum by the sebaceous glands due to increased blood levels of the androgen (male sex) hormones, such as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and testosterone [5,68,105] in:

- Newborns

- Adolescents

- Individuals with hormonal disorders, such as Cushing’s disease

- Increased sensitivity of the sebaceous glands to the androgen hormones due to:

- Genetic predisposition [105]

- Stress [102,103,104]

- Increased shedding of the cells (keratocytes) in the hair follicles [93]

- Overgrowth of otherwise normal skin bacteria Propionibacterium acnes in the hair follicles

- Inflammation [34]

Picture 1. Acne vulgaris: a blackhead and whitehead

(source: Wikimedia, CC license)

Diagnosis

A doctor can usually make a diagnosis of acne by a simple inspection.

High blood levels of androgen or other hormones can reveal the underlying disorder, such as Cushing’s disease.

Differential Diagnosis

The notable difference between acne and other conditions is the absence of blackheads in the later [17]:

- Insect bites can cause red itchy and tender bumps.

- Ingrown hair (folliculitis barbae, razor bumps) appears as red bumps on the shaved areas.

- Bacterial folliculitis (an inflammation of the hair follicles usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus) can cause red pimples anywhere on the body, including the face, inside of the nose or ear, scalp, trunk, buttocks, genitalia and limbs.

- Oil folliculitis is an inflammation of the hair follicles due to exposure to oils.

- Hot tub folliculitis caused by the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa appears as red bumps on the skin areas covered by the swimming suit.

- Pityrosporum folliculitis appears as red bumps as a reaction to the fungi Malassezia furfur.

- Ringworm (a fungal infection) can present with red or brownish scaly rash in the form of circular patches and occasional pus-filled bumps anywhere on the skin.

- Seborrheic dermatitis (skin inflammation by Malassezia fungi) appears as yellow greasy scales on the scalp, face and upper trunk.

- Dermatitis herpetiformis appears in some individuals with celiac disease as very itchy red blisters on the elbows, knees, back, buttocks and scalp, mainly in adults.

- Rosacea appears in flares with flushing or constant redness and occasional pus-filled bumps on the nose, cheeks, chin and forehead or, rarely, on neck and chest; it occurs after 30 and can be triggered by stress, alcohol or hot foods.

- Bumpy hives appears as an allergic reaction to foods or other irritants; pink itchy bumps appear and disappear within several hours.

- Milia (small epidermoid cysts)–collections of dead skin cells in the skin–appear as small white bumps on the nose, cheeks and around the eyes, mainly in infants, but also in adults.

- Sweat rash, prickly heat or miliaria (sweat gland clogging triggered by heat) appears as red itchy bumps in the armpits, groin or face.

- Facial demodicosis, caused by Demodex mites, appears as red bumps on the face.

- Keratosis pilaris (thickened hair follicles filled with skin cells) appears as skin-colored, red or brown non-itchy bumps, mainly on the upper arms or thighs.

- Molluscum contagiosum is a viral infection that appears as small (2-3 mm) red fleshy bumps anywhere on the skin.

- Perioral dermatitis is a skin inflammation with red bumps around the mouth (limited to the chin and nasolabial folds).

- Sebaceous hyperplasia is a sebaceous gland overgrowth that appears as yellowish or skin colored bumps on the face in middle-aged or older people.

- Other skin cysts

- Hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa is an inflammation in armpits, groin or below the breasts with underskin bumps covered by a red rash, which can ooze pus.

- Angiofibromas are small (1-3 mm) flesh-colored bumps on the nose and cheeks.

- Syringoma are small benign tumors of the sweat glands that appear as clusters of skin-colored bumps, mainly below the eyes.

- Leprosy is a rare bacterial infection that appears as skin-colored bumps and lumps.

- Chloracne can appear after inhalation, ingestion or contact with dioxin as a sudden eruption of skin-colored bumps and underskin cysts on the face and neck.

Treatment

1. Lifestyle Changes: Diet and Coping With Stress

Stress is a possible trigger of acne. If your life is disorganized, it can help you clear acne, if you adopt regular eating, working and sleeping pattern.

It has often been proposed that foods high in sugar and quickly absorbable carbohydrates (soda, sweets, white bread, white rice, potatoes) and milk can aggravate acne. It can help you if you limit these or any other foods you suspect they trigger acne in your case–the most probable candidates are those foods you think are not really necessary for you or make you feel uncomfortable or ashamed when you eat them.

Total fasting for few weeks can decrease the production of sebum by the sebaceous glands by 40% [54]. Recommending fasting to treat acne would be an exaggeration, but decreasing calorie intake (by overweight individuals) or avoiding very high-calorie foods (by anyone) might help clear cane.

2. Over-The-Counter Products, Supplements, Herbs and Home Remedies

OTC topical medicines are available in the form of gels, lotions, creams, soaps or pads. They can contain one or more medicines mentioned below. Those that are effective should help within 4-8 weeks [1,2].

Benzoyl peroxide destroys the bacteria Propionibacterium acnes in the skin. There is some WEAK EVIDENCE that benzoyl peroxide is effective in the treatment of mild and moderate acne [18,20,31,33,42,43,47,49]. Gels with 2.5%, 5% and 10% benzoyl peroxide seem to be equally effective [43]. According to one study review, 5.3% benzoyl peroxide in a foam form (to leave on) is effective in the treatment of mild to moderate back acne [44] and according to another review, benzoyl peroxide 6-8% wash (to apply and rinse) can be effective in the treatment of inflammatory and noninflammatory facial acne [46].

There is some WEAK EVIDENCE of the effectiveness of tea tree oil [15,26,27,28,29] and bee venom [15] in the treatment of mild acne.

There is INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE of the effectiveness in the treatment of acne for aloe vera [23,36], alpha hydroxy acid [23], antioxidants (vitamin A or retinol [31,36,79,87], beta carotene [34], vitamin C [34], vitamin E [77]), Ayurvedic or Chinese herbs [36], basil oil [36], bovine cartilage [14], brewer’s yeast [23,96], essential oils (chamomile, cinnamon, grapefruit, ginger, hibiscus, jasmine, lavender, lemon, mint, rose, thyme) [80,82], fish oil (omega-3 fatty acids) [72,73], hydrogen peroxide [59], linoleic acid [36], nicotinamide (vitamin B3) [30], Nigerian Toto [36], oligosaccharides from seaweed [69], pantothenic acid (by mouth) [75], prebiotics [92], probiotics [90], pyroxidine [36], resorcinol [2], salicylic acid (0.5-5%) [47,49], sulfur [38], resveratrol gel [78], tannins in herbal extracts (beard moss or usnea, Cannabis sativa, eucalyptus, green tea, licorice, mountain grapes, old man banksia, purple coneflower, rosemary, St.John’s-wort, witch hazel) [91], turmeric [82,97,101], vitex (for pre-menstrual acne) [82,96], zinc (topical or oral) [23,31,32,35] or yeasts, such as Saccharomyces bulderi [91].

There seems to be NO EVIDENCE of the effectiveness of the following home remedies in the treatment of acne when applied on the skin: apple cider vinegar, aspirin tablet, bacon, baking soda, banana peels, coconut oil, egg whites, honey, lemon juice, neem oil [58], orange peels, papaya, saliva, sea salt bath, steam cleaning, strawberries, tomatoes or toothpaste.

3. Prescribed Ointments

Prescribed ointments are intended for the treatment of moderate and severe acne.

Azelaic acid. There is some WEAK EVIDENCE of its effectiveness [39,40,41].

Salicylic acid (prescription-strength, 5-30%) is used as a chemical peel [1,5,37]. There is INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE of the long-term effectiveness of chemical peels in the treatment of acne [17].

Retinoids (vitamin A derivatives) include tretinoin, isotretinoin, adapalene and tazarotene. Tretinoin seems to be most effective [33]. Retinoids reduce sebum production, inflammation, shedding of the keratinocytes and bacterial colonization in the sebaceous glands [33].

Antibiotics, such as tetracycline, minocycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, trimethoprim, clindamycin, sulfacetamide or dapsone are intended for the treatment of inflammatory acne; they are probably not effective in mild noninflammatory acne (whiteheads and blackheads) [33]. They should always be used in combination with benzoyl peroxide, a topical retinoid or azelaic acid. They do not seem to be more effective than benzoyl peroxide alone [47]. There seem to be no clear differences in the effectiveness among different antibiotics [45]. Long-term antibiotic use can result in bacterial resistance [9].

Common side effects of acne ointments are skin dryness, redness, itching, burning, peeling, swelling and–with retinoids–the initial worsening of acne, increased risk of sunburn and skin thinning [33,94,95]. An allergic reaction with a severe itch and sudden appearance of pinkish bumpy or patchy hives may occur in sensitive individuals.

4. Drugs by Mouth

Oral drugs for moderate or severe acne [2,4,5]:

Antibiotics, such as doxycycline, erythromycin, minocycline, tetracycline or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, may help in inflammatory acne. There seems to be no clear benefit of antibiotic-zinc combination over antibiotics alone [33]. Tetracycline can cause yellow discoloration of the skin and (in children younger than 8 years of age) teeth and increases the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus, especially in women [33]. Minocycline can cause liver damage [33].

Isotretinoin is considered very effective in the treatment of moderate to severe acne [33,99]. It can also prevent the formation of scars [2]. It usually prescribed for 15-20 weeks. After the start of the treatment, acne may temporarily worsen.

Isotretinoin can have quite some side effects, such as cracked lips, mouth sores, dry or itchy skin, changes in skin color, skin peeling, hair loss, rash, excessive sweating, nosebleeds, voice changes, chest pain, depression, drowsiness, seizures, ringing in the ears, excessive thirst, frequent urination, difficulty breathing, fever, tiredness, diarrhea, blood in the stool and elevated triglyceride levels [24]. Symptoms of overdose include flushing, headache, vomiting, dizziness and loss of coordination [24]. You should not buy isotretinoin via the internet and always use it under the doctor’s supervision.

In the United States, women who want to use oral retinoids need to get involved in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved monitoring program iPLEDGE, which includes regular pregnancy tests and use of contraceptive pills to prevent birth defects.

Do not take isotretinoin if you are or can become pregnant, you are breastfeeding or taking tetracycline antibiotics or you are allergic to isotretinoin [25].

A common current approach to acne treatment with medicines [17,33]:

- Mild acne: OTC ointments containing benzoyl peroxide

- Moderate acne: topical retinoids plus topical antibiotics plus benzoyl peroxide or azelaic acid

- Severe acne: oral retinoids and oral antibiotics plus benzoyl peroxide

NOTE: You should continue with any acne treatment for at least 2 or 3 months before deciding if it works or not [5]. A combination of various medicines is usually more effective than any single medicine. Discuss with a dermatologist which combination is most appropriate for you.

5. Dermatologic Procedures

There is INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE of the effectiveness of the following therapies for acne [17]:

- Light therapy with blue or red light, photodynamic therapy or green or yellow laser [7,8,19]

- Chemical peels (using glycolic acid [36,57], lactic acid, salicylic acid, Jessner’s solution or trichloroacetic acid)

- Extraction of blackheads and whiteheads

- Drainage and extraction of large cysts

- Microdermabrasion

- Acupuncture [15,21]

- Cupping [15,21]

- Cryotherapy [8]

- Exposure to the sun [7]

6. Treatment of Acne in Pregnancy

In women, acne can worsen in early in pregnancy–probably due to increased estrogen and testosterone levels–and tend to become milder in late pregnancy [57].

Preferably, pregnant women should not use any drugs to treat acne. The following is considered safe during pregnancy [11]:

- Benzoyl peroxide

- Azelaic acid

- Glycolic acid

- Low-concentration salicylic acid preparations

- Light and laser therapy

DO NOT use the following in pregnancy [5,11]:

- Oral retinoids (isotretinoin can cause severe birth defects or miscarriage)

- Topical retinoids: tretinoin, isotretinoin and adapalene

- High-concentration (>5%) salicylic acid

- Antibiotics, especially tetracyclines (doxycycline, minocycline, lymecycline), cotrimoxazole or fluoroquinolones

Acne Prevention

The following may help [2,8]:

- Learn how to cope with stress.

- Regularly wash the face with warm (not hot) water.

- Do not pick, pop or squeeze acne and avoid touching your face with the hands.

- Regularly shampoo your hair.

- Use only alcohol-free cleansers. Apply the cleanser gently with the fingertips, not by a cloth or sponge.

- Avoid oil-based cosmetics.

- Avoid tanning beds and exposure to strong sunlight.

- Avoid humid environments, like unventilated kitchens, saunas or vacation in tropics.

Diet

Some studies suggest that avoiding high-glycemic index load diets (soda and other foods high in sugar, white bread and other goods made from white flour, white rice, potatoes) [60,61,62,65,67,73,87] and dairy products (milk [64,67,86], ice cream [67], cheese [60,84] or protein-calorie supplements (whey) [63,81,83] may help prevent acne.

There is INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE of the effectiveness of the high-fiber [73,87] or vegetarian diet [81] in the prevention or treatment of acne.

Infantile and Childhood Acne

In infants and small children between 6 months and 3 years of age, most commonly in boys acne are usually caused by genetic factors rather than hormonal abnormalities. They are usually mild or moderate, they typically appear on cheeks and resolve in few months [12].

In children, 3-6 years of age, acne are more likely caused by increased levels of androgen hormones due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing syndrome, 21-hydroxylase deficiency, precocious puberty or androgen-secreting tumors [12]. Associated symptoms include excessive body hair, abnormal growth and premature genital and breast development.

Treatment is usually topical with benzoyl peroxide or erythromycin gel [12,22]. In severe acne, oral antibiotics, such as erythromycin and trimethoprim, or isotretinoin can be used [12,22].

Adult Acne

Adult acne is either acne that persists from adolescence or new-onset acne after the age of 25. They are more common in women than in men and can persist after the age of 30 or even 40. Triggers can include psychological stress, cigarette smoking [56] and excessive alcohol drinking [76].

Summary

You may be able to prevent or limit acne by:

- Adopting regular eating, working and sleeping patterns

- Reducing psychological stress by solving eventual relationship- and work-related conflicts

- Avoiding foods with high glycemic index (sugary drinks, potatoes, white rice, white bread) and milk.

The most effective medications for mild acne seem to be the ointments containing benzoyl peroxide (available without prescription) and for moderate and severe acne tretinoin ointments and isotretinoin capsules (by prescription).

You should not expect to get rid of acne fast or even overnight, but only about a month or two after the onset of treatment.

- References

- Acne: overview American Academy of Dermatology

- Questions and answers about acne National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Davidovici BB et al, 2010, The role of diet in acne: facts and controversies PubMed

- Acne DermNet.nz

- Graber E, 2015, Patient Information: acne (beyond the basics) UpToDate

- What causes acne? DermNet.nz

- Lasers, lights and acne DermNet.nz

- Acne management DermNet.nz

- Topical treatment for acne DermNet.nz

- Acne due to medicines DermNet.nz

- Acne in pregnancy DermNet.nz

- Infantile acne DermNet.nz

- Acne fulminans DermNet.nz

- PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board, 2016, Cartilage (Bovine and Shark) (PDQ®), PubMed Health

- Cao H et al, 2015, Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris Cochrane

- Abdel Hay R et al, 2016, Treatment for acne scars Cochrane

- Titus S et al, 2012, Diagnosis and Treatment of Acne American Family Physician

- Mohd Nor NH et al, 2013, A systematic review of benzoyl peroxide for acne vulgaris PubMed

- Hamilton FL et al, 2009, Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: systematic review PubMed

- Lamel SA et al, 2015, Evaluating clinical trial design: systematic review of randomized vehicle-controlled trials for determining efficacy of benzoyl peroxide topical therapy for acne PubMed

- Hui-Juan C et al, 2013, Acupoint Stimulation for Acne: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials PubMed Central

- Rao J, Acne vulgaris guidelines Emedicine

- Acne: Are there any effective natural acne treatment options? Mayo Clinic

- Isotretinoin MedlinePlus

- Isotretinoin Drugs.com

- Tee tree oil National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

- Enshaieh S et al, 2007, The efficacy of 5% topical tea tree oil gel in mild to moderate acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study PubMed

- Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia), evidence Mayo Clinic

- Ernst E et al, 2000, Tea tree oil: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials PubMed

- Shahmoradi Z et al, 2013, Comparison of topical 5% nicotinamid gel versus 2% clindamycin gel in the treatment of the mild-moderate acne vulgaris: A double-blinded randomized clinical trial PubMed Central

- Decker A et al, 2012, Over-the-counter Acne Treatments PubMed Central

- Brandt S et al, 2013, The clinical effects of zinc as a topical or oral agent on the clinical response and pathophysiologic mechanisms of acne: a systematic review of the literature PubMed

- Purdy S et al, 2011, Acne Vulgaris PubMed Central

- Bowe WP et al, 2010, Clinical implications of lipid peroxidation in acne vulgaris: old wine in new bottles PubMed Central

- Zinc, evidence Mayo Clinic

- Magin PJ et al, 2006, Topical and oral CAM in acne: a review of the empirical evidence and a consideration of its context PubMed Health

- Lee HS et al, 2003, Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients PubMed

- Del Roso JQ, 2009, The Use of Sodium Sulfacetamide 10%-Sulfur 5% Emollient Foam in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris PubMed Central

- Iraji F et al, 2007, Efficacy of topical azelaic acid gel in the treatment of mild-moderate acne vulgaris PubMed

- Worret WI et al, 2006, Acne therapy with topical benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics and azelaic acid PubMed

- Gollnick HP et al, 2004, Azelaic acid 15% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Combined results of two double-blind clinical comparative studies PubMed

- Warner GT et al, 2002, Clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel: a review of its use in the management of acne PubMed

- Sagransky M et al, 2009, Benzoyl peroxide: a review of its current use in the treatment of acne vulgaris PubMed

- Bikowski J, 2010, A Review of the Safety and Efficacy of Benzoyl Peroxide (5.3%) Emollient Foam in the Management of Truncal Acne Vulgaris PubMed Central

- Garner SE et al, 2003, Minocycline for acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety PubMed

- Del Roso JQ et al, 2008, What is the Role of Benzoyl Peroxide Cleansers in Acne Management? PubMed Central

- Seidler EM et al, 2010, Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide with salicylic acid, and combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in acne PubMed Health

- Ayer J et al, 2006, Acne: more than skin deep PubMed Central

- Shalita AR, 1989, Comparison of a salicylic acid cleanser and a benzoyl peroxide wash in the treatment of acne vulgaris PubMed

- Zouboulis CC, 2004, Acne and sebaceous gland function PubMed

- Makrantonaki E et al, 2011, An update on the role of the sebaceous gland in the pathogenesis of acne PubMed Central

- 2013, Corticotrophin-releasing hormone You and Your Hormones

- Fudge EB et al, 2009, Cushing Syndrome in a 6-Month-Old Infant due to Adrenocortical Tumor PubMed Central

- Pochi PE et al, 1970, Sebaceous Gland Response in Man to Prolonged Total Caloric Deprivation Journal of Investigative Dermatology

- Dessinioti C et al, 2009, Congenital adrenal hyperplasia PubMed Central

- Capitanio B et al, 2009, Acne and smoking PubMed Central

- Sharad J et al, 2013, Glycolic acid peel therapy – a current review PubMed Central

- Kumar VS et al, 2007, Neem (Azadirachta indica): Prehistory to contemporary medicinal uses to humankind

PubMed Central - Milani M et al, 2003, Efficacy and safety of stabilised hydrogen peroxide cream (Crystacide) in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris: a randomised, controlled trial versus benzoyl peroxide gel PubMed

- Jung JY et al, 2010, The influence of dietary patterns on acne vulgaris in Koreans PubMed

- Katta R et al, 2004, Diet and dermatology PubMed Central

- Smith RN et al, 2007, The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial PubMed

- de Carvalho Pontes T et al, 2013, Incidence of acne vulgaris in young adult users of protein-calorie supplements in the city of João Pessoa – PB PubMed Central

- Adebamowo CA et al, 2008, Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys PubMed Central

- Smith RN et al, 2007, A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

- Reynolds RC et al, 2010, Effect of the Glycemic Index of Carbohydrates on Acne vulgaris PubMed Central

-

Ismail NH et al, 2012, High glycemic load diet, milk and ice cream consumption are related to acne vulgaris in Malaysian young adults: a case control study PubMed Central

- Lai JJ et al, 2012, The Role of Androgen and Androgen Receptor in the Skin-Related Disorders PubMed Central

- Capitanio B et al, 2012, Randomized controlled study of a cosmetic treatment for mild acne PubMed

- Chiu A et al, 2003, The response of skin disease to stress: changes in the severity of acne vulgaris as affected by examination stress PubMed

- Yosipowitch G et al, 2007, Study of psychological stress, sebum production and acne vulgaris in adolescents PubMed

- Khayef G et al, 2012, Effects of fish oil supplementation on inflammatory acne PubMed Central

- Bowe WP et al, 2010, Diet and acne PubMed

- Melnik BC, 2015, Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: an update PubMed Central

- Yang M et al, 2014, A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of a Novel Pantothenic Acid-Based Dietary Supplement in Subjects with Mild to Moderate Facial Acne PubMed Central

- Higgins EM et al, 1994, Cutaneous disease and alcohol misuse PubMed

- Vitamin E evidence Mayo Clinic

- Fabbrocini G et al, 2011, Resveratrol-containing gel for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a single-blind, vehicle-controlled, pilot study PubMed

- Ruamrak C et al, 2009, Comparison of clinical efficacies of sodium ascorbyl phosphate, retinol and their combination in acne treatment PubMed

- Zu Y et al, 2010, Activities of ten essential oils towards Propionibacterium acnes and PC-3, A-549 and MCF-7 cancer cells PubMed

- Melnik B, 2012, Dietary intervention in acne, Attenuation of increased mTORC1 signaling promoted by Western diet PubMed Central

- Sinha P et al, 2014, New Perspectives on Antiacne Plant Drugs: Contribution to Modern Therapeutics PubMed Central

- Silverberg NB, 2012, Whey protein precipitating moderate to severe acne flares in 5 teenaged athletes PubMed

- Adebamowo CA et al, 2005, High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne PubMed

- Kaymak Y et al, 2007, Dietary glycemic index and glucose, insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3, and leptin levels in patients with acne PubMed

- Adebamowo CA et al, 2006, Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls PubMed

- Kucharska A et al, 2007, Significance of diet in treated and untreated acne vulgaris PubMed Central

- Caperton C et al, 2014, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study Assessing the Effect of Chocolate Consumption in Subjects with a History of Acne Vulgaris PubMed Central

- Vongraviopap S et al, 2016, Dark chocolate exacerbates acne PubMed

- Bowe WP et al, 2011, Acne vulgaris, probiotics and the gut-brain-skin axis – back to the future? PubMed

- Nasri H et al, 2015, Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: A Review of Recent Evidences PubMed Central

- Patel S et al, 2012, The current trends and future perspectives of prebiotics research: a review PubMed Central

- Ottawiani M et al, 2010, Lipid mediators in acne, review article Hindawi

- Tretinoin topical, side effects WebMD

- Isotretinoin gel for acne (Isotrex) Patient.info

- Shenefelt PD, Chapter 18 Herbal Treatment for Dermatologic Disorders Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, 2nd edition

- Turmeric WebMD

- Zaba R, Acne fulminans overview Emedicine

- Leyden JJ et al, 2014, The Use of Isotretinoin in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris,

Clinical Considerations and Future Directions PubMed Central

- Acne vulgaris Epocrates

- Vaughn et al, 2016, Effects of Turmeric (Curcuma longa) on Skin Health: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence PubMed

- Zouboulis CC, 2004, Acne and sebaceous gland function PubMed

- Makrantonaki E et al, 2011, An update on the role of the sebaceous gland in the pathogenesis of acne PubMed Central

- 2013, Corticotrophin-releasing hormone You and Your Hormones

- Degitz K et al, 2007, Pathophysiology of acne Wiley Online Library

Very informative article! Thanks for sharing this great article with us. This is the best article I’ve read about acne. I really like the post and found very helpful for and everyone who really didn’t know much about acne. Thanks for sharing this.

Indeed, it is very common!

The most spread simple reasons were listed in the article, and moreover i was said that one of it may be some bacteria trapped into your butt pores. Not a big thing, but the most common ones appear in form of small bumps on the skin that resemble acne. They however are not considered typical acne.

An excellent article! Probably the best I’ve read about acne, very well articulated and helpful! Thank you 🙂

Hi there! This article is very educational. I’ve learned a lot from this read! Many people got Acne in their genes but do not know what to do about it and mostly think they just disappear in time. Thanks to this blog people can become more informed of how to manage and minimize the acne outbreaks. You’ve got a very helpful site!